SOCIAL ENTERPRISE

&

THE DEPRIVED

Successful Social Enterprise

The success of a social enterprise is again difficult to define as a result of what it means to be socially good as well as how different stakeholders perceive it. Look at Cho's (2006) Ecotourism case by clicking here to understand why this is.

If there is an answer to social enterprise being the solution, then we must first look at its success in catering for the deprived.

There are a number of points which affect the idea of success for a social enterprise:

-

Mission-based impact is main criterion to judge enterprise’s success, not wealth creation

-

Although the definition is notconcrete, the main aim of socialentrepreneurs is to pursue social goals and create social impact

-

As Dees & Marion (1988) outline, “wealth is just a means to an end for social enterprises”

-

Successful social enterprises aim to be profitable and self-sustaining, but also to accomplish predefined social goals

However there is an inherent problem with this as the field of social enterprise is yet to establish a common understanding of “social impact” – What it is and how to measure it?

The Grameen Bank offers a successful case of social entrepreneurship but even so it is rooted in the short term and have inherent problems about how social it truly is as there are issues of a political nature, along with gender issues and violence. This is explained here along with a number of critiques which begs the question: Is this really a model of a successful social enterprise?

The Diamonds in this graph assess the criteria for success and failure in social enterprises. They have been adapted from Shenhar and Dvir (2007) diamond models, which generate understanding of project success and failure.

In terms of social enterprise success, we have identified four key drivers, these are shown on the axes of the graph. Evidently, this diamond shows that where the diamond is bigger, a greater perception of success can be achieved. Failure on this graph, or little success will then be founded upon a smaller diamond.

Failure in Social Enterprise

The social enterprise literature is dominated by stories of good practice and heroic achievement. Failure has not been widely researched. The limited policy and practice literature presents failure as the flipside of good practice. Explanations for failure are almost wholly individualistic, and related to poor governance. However, organisational studies literature shows that failure cannot be understood without reference to the wider environment within which organisations operate. We show that simple individualistic explanations are not sufficient by which to understand social enterprise failure and outline the implications for academic understanding of social enterprise (Duncan and Teasdale, 2012)

One example of failure that has been documented is the Aspire case study found here. It documents why it is important to look at failure, as failure means we can learn for the future. It also looks at the inherent problems of replication and scalability, making a business model unapplicable in different areas. Although the catalogue business is now defunct, Aspire's values continue to live on through the Aspire Foundation. To read more about them, click here

Interestingly, around 8 of every 10 small businesses fail in their first year (Forbes, 2013). This is the same for social enterprises so a substantial number of social enterprises fail. However, these remain an undocumented facet within recent discourse, which begs the question, how do we learn from these mistakes? As social entrepreneurs experiment with new organizational forms, learning from others’ mistakes may be just as important as learning from successful cases.

The Diamonds in this graph assess the criteria for success and failure in social enterprises. They have been adapted from Shenhar and Dvir (2007) diamond models, which generate understanding of project success and failure.

In terms of social enterprise failure, we have identified four key drivers, these are shown on the axes of the graph. This graph shows that when the Aspire business model is expanded into different areas and a focus on national application is incorporated, a problem with cash flow arose. Evidently, this graph shows that before the business was franchised it was relatively successful represented by a bigger diamond. Following the expansion, the business model became inapplicable and this is represented by the smaller diamond.

Critical Thoughts

According to Dees, social entrepreneurs ‘attack the underlying causes of problems, rather than simply treating symptoms’ (Dees, 2001). Yet by construction this appears to be untrue in cases where problems are rooted in politics, not market failure (Cho, 2006). Similarly, there is a danger that social entrepreneurship might end up addressing the symptoms of the capitalist system rather than its root causes [Edwards in (Dey & Stayaert, 2012)]. These ideas tie back to social enterprise being the solution where the state, market and voluntary sector have failed. However, based on this, it appears social enterprise cannot seek to solve issues where the root cause is inherently political.

'Throughout the discourse, social entrepreneurship is overtly posited as the panacea to failure in market and state mechanisms. In this, it is explicitly manoeuvred into a technocratic function of serving underserved parts of society, where people engaged in social entrepreneurship take on a palliative role. This managerially defined position, marked by a general emphasis on performance, impact, efficiency and sustainability, detracts from a more politicalideological function. It simultaneously disarms the ‘third sector’ of radical approaches to civil society and maintains the distance between state and parts of society served by social entrepreneurship' [Cho in (Parkinson & Howorth, 2008: 292)]. As a result of this, social enterprise can end up being more problematic than at first glance, as it ends up on a pedestal and other solutions take a back seat.

Also noted by Parkinson & Howorth (2008: 292), the preoccupation with social enterprise has resulted in a sense of elitism, reflected in current preoccupations with, for example, how to spot potential and back the winners. This also creates tension as a focus on the individual entrepreneur can result in an elite whose focus is switched to their own preconceptions of what is social. This can then be tied back to Salamon's (1987) idea of Philanthropic Paternalism, which is tied within voluntary market failure, as the backing of the enterprise is likened to the interests of the entrepreneur at the helm. However, Parkinson & Howorth (2008) note that a movement to the collective is beginning to take focus and issues with the individual entrepreneur diminishes. If the collective are taken into account, then does this offer social enterprise as a solution to the deprived?

Summary

Success and failure are rooted into any organisational form. A common theme has been neglected within recent discourse that shows failure as absent (Teasdale, 2011). We can tie failure back to the aim of social enterprise in that it aims to tackle root causes as opposed to addressing symptoms. As this belief is rooted in being the solution to market, state or voluntary failure, then social enterprise neglects the idea that it is outside the bounds of where it can tackle a root cause when the cause is inherently political and embedded within the state or market .The Grameen Bank has been used an an example of success. Taken at face value, it looks to offer a solution in local areas of providing micro-finance. However, a closer look at both the roots of the enterprise and the roots of the problem depicts a different question which questions the successfulness of this particular social enterprise.

Another route to helping the deprived comes in the form of Corporate Social responsibility (CSR). CSR is a mechanism in which the traditional enterprise attempts to tackle the deprivation issue. As shown in its critique, CSR is focussed upon economic gain. This paves the way for social enterprise that attempts to create a new form of economy, that responds to a different rationality than the traditional organisation (Ridley-Duff, 2008). With this in mind, social enterprise attempts to situate itself at the top of the Model of Corporate Moral Development pyramid, with a central ethical stance.

However despite its potential, social enterprise may be seen only as a cosmetically satisfying solution (Cho, 2006) rather than living up to its potential, if it remains an entity by itself. This relates back to state and market failure, by which social enterprise can fall foul of addressing symptoms as opposed to root causes. Despite this, social enterprise attempts to engage in activities at the bottom of the pyramid in order to draw a successful outcome. As institutional theory stipulates, social enterprise will begin to merge with both the state and the market, creating a partnership in which to address the bottom of the pyramid with both the right and ethical means. As a result success can only be drawn when the ideas of the market, state and social entrepreneurs are aligned. As we can see from the Aspire case study where Aspire was franchised as a profit making business which in turn foresaw its closure. This asks the question, can we replicate a successful enterprise in a different deprived community? The answer is entirely based upon context as context prevents a best practice approach, which limits the replication of solutions (Seelos et al., 2006). This affects the scalability of social enterprises as they fall foul of the ability to grow. As a result, social enterprise may only provide solutions at a local level and as a result 'avoid discursively mediated processes that could produce more inclusive and integrative systemic solutions' (Cho, 2006).

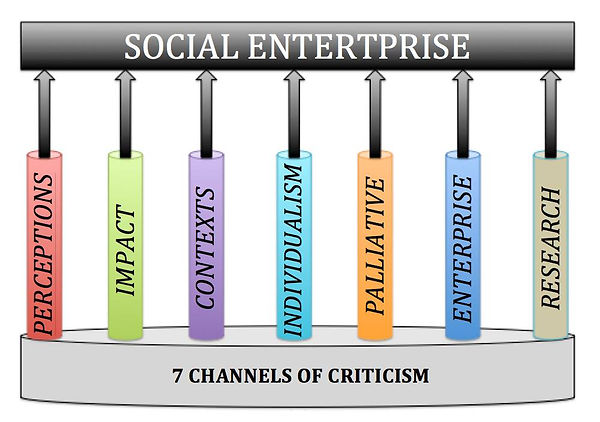

A model has been created to posit the main criticisms of social enterprises that we have uncovered throughout these case studies. Evidently, it is all contextual and different perceptions influence the success criteria for a social enterprise. We then run into difficulties around impact analysis and how this is possible. The individualism aspect also plays its role which may be problematic as social enterprise should adhere to the collective and not the unsung hero. Also, as Cho (2006) posited, social enterprise may play a more palliative role as opposed to addressing the root cause. Similarly, it neglects enterprise from discourse as a possible solution and stipulates the solution must be founded upon social enterprise. As a result, there is not enough research which uncovers the success and failure criteria for a social enterprise.

Points adapted from MacDonald et al (2011)