SOCIAL ENTERPRISE

&

THE DEPRIVED

Theories

1

Quadruple Bottom Line

The QBL originates from the Triple Bottom Line introduced by Elkington in 1994.

This model highlights the importance of a company having four bottom lines:

-

Profit: economic value and benefit of business practices

-

Purpose: The spirituality and faith – positivity on society as a whole

-

Planet: business practices that are environmentally sustainable

-

People: business practices that are beneficial towards human labour and communities where the business operates

Critique:

-

Hard to measure success of bottom lines

-

Companies are not held accountable

-

Model focuses on co-existence not interdependence

-

However, Social Accounting & Audit (SAN, 2015) allows a framework to help measure social value

Application:

The quadruple bottom line can be used as a defining concept for constituting a social enterprise. Both the double bottom line and triple bottom line have attempted to do this, but this has come under criticism for being to broad. We offer the quadruple bottom line as a more defining concept for 'Social Enterprises' for its inclusion of purpose, as this has the ability to separate it further from a traditional organisation.

2

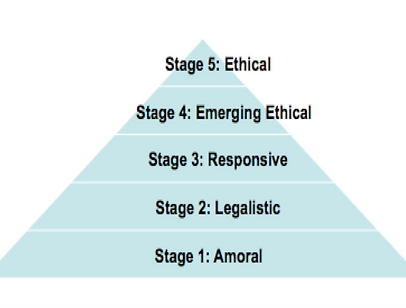

Corporate Moral Development

The Model of Corporate Moral Development was introduced by Reidenbach and Robin (1991).

This model identified how ‘ethical’ a company is in 5 different stages:

Amoral - Anything goes just make the profit

Legalistic – We need to follow the law

Responsive – Responding to incidents – learn from experience

Emerging ethical – Policy driven - starts to be part of the company’s decision-making

Ethical – Embedded in a companies mission, vision and values

Critique:

-

Pyramid does not appreciate overlapping nature of the domains

-

Difficult to clearly categorize organisations as some areas of a business may fit into one category where as other business fit into another

Application:

This model can be applied to both social enterprises and enterprises. It can be stipulated that a social enterprise should reside at the top of the pyramid whereas normal enterprise will reside between the different levels.

Four Components of CSR

‘We define CSR as situations where the firm goes beyond compliance and engages in actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law’ (McWilliams et al, 2006)

3

Critique:

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game” (Friedman, 1973)

CSR allows businesses to benefit from the use of transfer pricing, tax havens, tax evasion or abuse of market power (Castresana, 2013)

Application:

"There are a number of reasons for doubting the claim that adopting CSR will make growth more inclusive and, more equitable, and thereby reduce poverty” (Jenkins, 2005). Similarly Frynas (2005, 2008) concludes that CSR is based on the business case, and that social activities are there to widen business opportunities. What this results in can be linked to market failure where another solution, perhaps in the form of social enterprise, can solve something CSR is unconcerned about as a result of its economic disposition.

4

State and Market Sector Failure

Inherent limitations in both the private market and government as providers of "collective goods" (Weisbrod 1978).

- Where collective goods are a necessity, the market will fail, as economics will draw them into short supply. There is also the problem of 'free riders' who will enjoy collective goods even if they have not paid

- The Government can overcome the free rider problem through taxes but they have issues of their own:

'In a democratic society it will produce only that range and quantity of collective goods that can command majority support. Inevitably, this will leave some unsatisfied demand on the part of segments of the political community that feel a need for a range of collective goods but cannot convince a majority of the community to go along' (Salamon, 1987: 8)

Khanin explains social entrepreneurship as a potential approach to offset market failures caused by the tragedies of disharmonization. These tragedies may lead to overconsumption (caused by the tragedy of the commons), underinvestment (caused by the tragedy of the anti-common), or strategic behavior (caused by the tragedy of the semi-commons) (Zeyen et al., 2012). Social Enterprise appears then to be able to help mitigate both state and market failure.

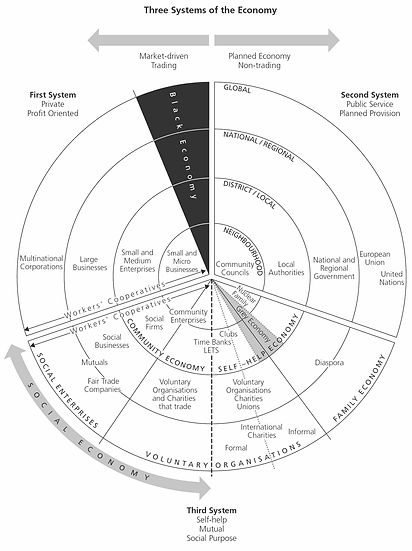

Pearce places social enterprise within the tertiary system that is market driven. Also, 'Pearce’s model also shows the diversity and complexity of the social economy. The umbrella term ‘SE’ also covers a range of organizational types that vary in terms of size, legal structure, activity, geographic scope, income sources, motivations, level of profit orientation, relationship with communities, ownership and culture'

Critique:

-

Nations with bigger states tend to have a higher volume of volunteers (cultural), e.g. Sweden has more volunteers

-

Conflicts with literature: suggest smaller states would have need for more charities and volunteers

-

In democracy, government has limitation as producer of collective goods (can only supply services majority want, creating unsatisfied demand for small groups)

Application:

Discourse has followed a trend in that 'social enterprise' is the answer to state and market failure

'Throughout the discourse, social entrepreneurship is overtly posited as the panacea to failure in market and state mechanisms. In this, it is explicitly manoeuvred into a technocratic function of serving underserved parts of society, where people engaged in social entrepreneurship take on a palliative role' (Cho 2006). As a result, Social enterprise cannot solve a problem that is rooted in politics, if it is to take on a single identity.

Taken from (Pearce, 2003)

5

Institutional Theory:

'Dart (2004), who argues that the legitimacy of social enterprise is not derived from any rational assessment of results. Instead, social enterprise’s legitimacy derives from a society’s wider fixation with business ideology and a belief that the market knows best' (Teasdale, 2011: 8)

'Institutional theory predicts that organisations in a given industry will adopt the dominant practices of the field rather than maintaining a distinctive identity' [Di Maggio and Anheier in (Teasdale, 2011: 8)]

Application:

'Rather than seeing the nonprofit sector and the state as substitutes, empirical evidence suggests that they should be seen as complementary – as state spending increases so does the size of the nonprofit sector' (Teasdale, 2011: 8)

Following from Voluntary Sector failure, this idea posits that social enterprise is embedded between state and market, rather than taking on its own form within the third sector.

Voluntary Sector Failure:

'In short, for all its strengths, the voluntary sector has a number of inherent weaknesses as a mechanism for responding to the human-service needs of an advanced industrial society. It is limited in its ability to generate an adequate level of resources, is vulnerable to particularism and the favoritism of the wealthy, is prone to self-defeating paternalism, and has at times been associated with amateur, as opposed to professional, forms of care' (Salamon, 1987: 42)

Institutional Theory & Voluntary Sector Failure

6

Bottom Of the Pyramid (BoP)

Prahalad (2002)

'In recent years, the emphasis on the role of the private sector in development is clearly shifting towards so-called “inclusive business” or “business at the base of the pyramid”' (Castresana, 2013: 253)

'The first version (BoP 1.0) set out from the consideration that poor people, given their situation of poverty and lack of access, formed a vast and unexplored potential market of unsatisfied consumers requiring goods adapted to their needs' (Castresana, 2013: 253).

BoP2.0 'enters its attention on several distinctive elements. To start with, it has a “bottom-up” logic in comparison with the previous version. It sets out from the premise that it is necessary to establish alliances with poor people, consider them not only as consumers but also as producers, and “co-create”, “co-invent” innovative business models alongside them. This idea of innovation is related to what Arora and Romijn (2009) call the “embedded innovation paradigm”' (Castresana, 2013: 254) The model on the right depicts this model of BoP so that it can draw successful social enterprise at the Bottom of the Pyramid.

Critique:

-

Business could end up generating dependency, manipulation and exploitation of the poor, pushing them to overconsumption (Karnani, 2007)

-

Poor lack power – model doesn’t provide a criteria for discerning how inclusive or empowering these practices are

-

Tragedy of the commons (Hardin, 1968)

-

Issues with infrastructure

-

Edward and Tallontire (2009) “a move away from the visible hands of political contestation into an arena where invisible hands predominate”

-

Coca-Cola malpractice in India: Click Here

Application:

The BoP approach allows a model in which social enterprise approach can target the bottom of the pyramid in order to draw success, where success can be perceived as creating social value. BoP is not restricted to social enterprise though and it offers a unique way in which inclusive business can work (Castresana, 2013). That is where inclusive business resides within the partnership between social enterprise, the public and the private.

Taken from (Pervez, Maritz & Waal, 2013)